Background

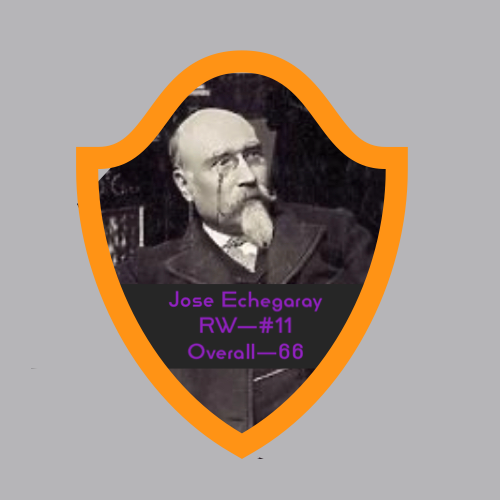

Jose Echegaray might have been the smartest person we’ve read about yet. He seems to have been able to do pretty much everything. He read classics by age 12, was an engineer, a diplomat, taught himself German so he could read philosophy treatises and was working on massive Mathematics textbooks when he passed away. Throughout that whole time he was also a writer, specifically of plays which many likened to an Iberian Ibsen*. He shared the 1904 honor with Frederic Mistral, but was honored for his unique works, including “the numerous and brilliant compositions which, in an individual and original manner, have revived the great traditions of the Spanish drama”

*Not to be confused with an Iberian Ibson, which would make them a Spanish substitute for local Minnesota legendary midfielder Ibson.

Works

Echegaray’s works are all high level 19th century melodrama, and were ideal for the early days of cinema (though mostly in Spain only). But he had a keen ear for conversations and confusions between characters, as shown in the piece I read for this project: Son of Don Juan.

Don Juan: What are you thinking of? Ah! Pardon! I must not disturb you.

Son of Don Juan, Act II aka You kids dealing with me in 10 years.

Lazarus: You don’t disturb me father. I was thinking of nothing important. My imagination was wandering, and I was wandering after it.

Don Juan: If you wish to work–to write–to read–and I trouble you I shall go. Ha. I shall go….Do you want me to go? for here I am…going.

Message

Echegaray’s style is…a bit much for a modern reader. He seems to have a penchant for melodrama in that, he wrote a bunch of melodramas. In the modern age, melodrama is a bit silly, a bit farcical and a bit easy to dismiss, but for a long time that was the style, and Echegaray did it better than almost anyone. For someone as immersed in complicated high brow pursuits as Echegaray clearly was it is apparent that he was, at the root of it all someone who had no shame in his feelings. It’s good to have big feelings.

Position: #11 Winger

Echegaray certainly seems to have been a thoroughly talented master of all trades, it would make him an excellent attacker who can link with other players, but the melodramatic tendencies make him also a prime candidate for Nobel FC’s resident flopper. I just picture someone touching his monocle chain and leaving Echegaray writhing in mid-air like a final tongue of smoke leaving a doused fire. While he was a life long Madrista, I have him in Oaxaca’s colors, as their flair for the dramatic look seems best for our purposes.

Am I too harsh on Echegaray? Do you think he belongs elsewhere, or at least would have been more of an engineer constructing things than a ham emoting all over the place?